Once pushed to the brink by habitat loss, persecution, and the pesticide DDT, the bald eagle was down to just a few hundred nesting pairs in the Lower 48 states by the 1960s. It remains one of the most dramatic raptor population crashes in modern North American wildlife history.

Today, their comeback is considered a landmark conservation success — one made possible by the Endangered Species Act, the ban on DDT, habitat protections, and decades of public pressure to do better. Their return proves what’s possible when science, policy, and people work in the same direction.

But recovery doesn’t mean the work is done. Bald eagles still face grave threats from lead poisoning, collisions, and disturbance around nesting sites. Continued protection of waterways and shoreline habitat remains essential if we want these birds to thrive for generations to come.

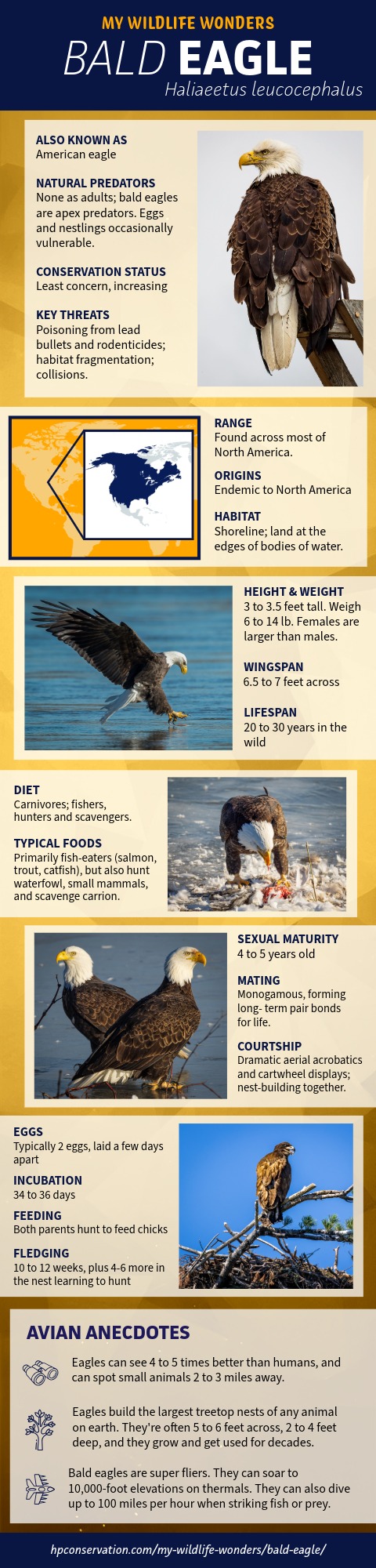

Species: Bald Eagle

Also Known As: American Eagle

Quick Facts About the Bald Eagle

- Order: Accipitriformes (Birds of prey)

- Family: Accipitridae (Hawks, eagles, and kites)

- Genus: Haliaeetus (Sea eagles)

- Species: Haliaeetus leucocephalus

- Subspecies & Varieties:

- Northern Bald Eagle (H. l. alascanus)

- Southern Bald Eagle (H. l. leucocephalus)

- Size & Weight:

- Females are larger, ranging from 10 to 14 lbs on the high end, standing about 3.5 ft. tall with a wingspan up to 7.5 ft.

- Males range from 6 to 10 lbs, standing about 3 ft. tall with a wingspan up to 6.5 ft.

- Lifespan: 20 to 30 years in the wild

- Appearance: Iconic white head and tail in adults, contrasting with a dark chocolate-brown body. They have a massive, bright yellow hooked bill and pale yellow eyes. Their heavy plumage consists of roughly 7,000 feathers, which are layered to provide both waterproofing and insulation in sub-zero temperatures. Juveniles, with their mottled brown appearance before getting a white head, are often confused with golden eagles.

- Beak & Talons: Eagles have powerful, two-inch long, razor-sharp curved talons designed for gripping and killing prey. They are capable of exerting immense crushing force relative to the eagle’s body size. Their beak is made of keratin and grows continuously throughout their life, requiring regular “feaking” (rubbing against branches or rocks) to keep it sharp and clean.

- Diet: Carnivores. Primarily piscivores (fish-eaters), feeding on salmon, trout, and catfish. They also hunt waterfowl, small mammals like rabbits, and frequently scavenge carrion. Their sharp, hooked beak and highly acidic digestive system allow them to process bone, scales, and fur.

- Commonly Seen With: Ospreys, frequently the “unwilling” providers of fish via kleptoparasitism. Crows, ravens, and gulls, who often follow eagles to scavenge leftovers from their kills.

- Natural Predators: Apex predators with no natural predators as adults. Eggs and nestlings are occasionally vulnerable to Great Horned Owls, raccoons, crows, and black bears if the nest is left unguarded.

Bald Eagle Range & Habitat

- Current Range: Found across most of North America, from Alaska and Canada throughout the contiguous United States and into Northern Mexico. Major population strongholds exist in Alaska, the Pacific Northwest, the Chesapeake Bay, and Florida.

- Origin: Endemic to North America. Unlike many other large North American fauna, the Bald Eagle evolved specifically on this continent, diverging from other sea eagles (Haliaeetus) during the Pleistocene.

- Elevation Range: Primarily found from sea level to 3,000 feet, but they are highly adaptable. They have more rarely been recorded at high-altitude mountain lakes up to 10,000+ feet during the summer breeding season, when the water remains open and the fish supply is stable.

- Habitat: Highly dependent on water “ecotones,” or the edges where land meets water. They prefer mature, old-growth forests adjacent to large, open bodies of water, like lakes, reservoirs, major rivers, and coastal estuaries, which provide ample prey and sturdy nesting sites.

- Role in Landscape: As an apex predator and scavenger, they regulate populations of fish and waterfowl, preventing overpopulation. By transporting fish carcasses from the water to their massive forest nests, they facilitate “nutrient cycling,” depositing nitrogen and phosphorus that fertilizes the surrounding soil and promotes forest growth.

- Seasonal Migration: Partial or “conditional” migration. Northern populations migrate south or toward ice-free coastlines only when their freshwater hunting grounds freeze over. They often follow “fish runs” or congregate where dam tailwaters keep the river from freezing.

Bald Eagle Mating

- Social Structure: Pair-centric. Unlike many herd animals, eagles are solitary or pair-bonded during the breeding season, maintaining exclusive nesting territories. Outside of breeding, they exhibit communal roosting behavior, gathering in large groups near winter food sources to conserve heat and share information about prey location.

- Sexual Maturity: 4 to 5 years old. This stage is visually signaled by the transition from mottled brown “immature” feathers to the distinctive white head and tail plumage, indicating the bird is ready to establish a territory and seek a mate.

- Mating System: Monogamous. They form long-term pair bonds that typically last for life. If one mate dies, the survivor will usually find a new partner, but as a pair, they operate as a dedicated team for nest defense and chick-rearing.

- Mating Season: Regionally variable. In southern climates (Florida), the breeding cycle begins in October and November. In northern regions (Alaska and Canada), it occurs in late winter or early spring, typically February through April.

- Courtship: Pairs engage in dramatic aerial acrobatics to strengthen bonds. Key behaviors include the “Cartwheel Display” (locking talons at high altitudes and spinning toward the earth), mutual high-altitude soaring, and “duetting,” where the pair calls to one another while perched. Extensive nest-building, including adding massive sticks to their aerie, is also a core part of their pair-bonding ritual.

Bald Eagle Reproduction

- Incubation: About 34 to 36 days. The embryo develops within a hard-shelled egg. Both parents share the duty of sitting on the eggs to keep them at a consistent temperature.

- Hatching: Typically occurs in early to mid-spring, depending on the latitude. A pair typically lays two eggs, but one to three is possible. The eggs are laid a few days apart, meaning the chicks can hatch at different times. The young remain in the nest for about 10 to 12 weeks before “fledging” (taking their first flight).

- Chicks At Birth: Weighing only about 3 ounces (85 grams), “eaglets” are born helpless and covered in light-gray downy feathers. Their primary defense is the height and inaccessibility of the aerie. For the first two weeks, one parent (usually the female) “broods” the chicks constantly to protect them from cold and rain while the other hunts.

- Nest Management: Once the eaglets are about 3 to 4 weeks old and can regulate their own body temperature, both parents begin hunting simultaneously to meet the chicks’ massive food demands. The parents are fiercely territorial and will dive-bomb any intruder, including other eagles, that comes near the nesting tree.

- Feeding: Eaglets grow incredibly fast, reaching nearly full adult size in just 8 to 10 weeks. They are fed high-protein pieces of raw fish and meat delivered by the parents. Initially, the parents tear the food into tiny bits, but by 6 weeks, the chicks begin to “mantle” (cover their food with their wings) and tear at prey themselves.

- Fledging & Foraging: Young eagles leave the nest, or fledge, at roughly 10 to 12 weeks old, but they’re not yet expert hunters. They often stay near the nest for another 4 to 6 weeks, begging for food from the parents while practicing their flight and “snatching” maneuvers. They transition from parent-provided meals to scavenging and eventually independent hunting by late summer or fall.

Bald Eagle Conservation Status

“Least Concern,” “Increasing”

(Last assessed by the IUCN in 2021)

Once common across North America, Bald Eagle populations plummeted to the brink of extinction in the mid-20th century. While historical habitat loss and hunting played a role, the primary cause of the collapse was the widespread use of the synthetic pesticide DDT. The chemical accumulated in the food chain, causing eagles to lay eggs with shells so thin they would break under the weight of the incubating parents. By 1963, only 417 nesting pairs were left in the lower 48 states.

Following the federal ban on DDT in 1972 and the protections provided by the Endangered Species Act (ESA), the species staged a dramatic recovery. In 2007, the Bald Eagle was successfully removed from the Endangered Species List. Today, there are an estimated 316,000+ individual birds across the United States. While it is a premier conservation success, the species remains federally protected and requires ongoing monitoring to manage modern environmental risks.

Bald Eagle Conservation Efforts

- The Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act (1940): This law provides strict federal protection, making it illegal to disturb, harm, or kill eagles, their nests, or their eggs. It remains the primary legal safeguard for the species today.

- DDT Ban & Habitat Restoration: The 1972 ban on DDT allowed for the natural thickening of eggshells and a surge in successful hatches.

- The Clean Water Act helped restore the health of the rivers and lakes that eagles depend on for fish, their primary food source.

- Reintroduction Programs: During the 1980s and 90s, wildlife agencies successfully raised and released young eaglets from stable populations into areas where they had been extirpated, such as New York and the Tennessee Valley. Because the recovery was so robust and widespread, the North American population maintains high genetic diversity.

- Citizen Science & Community Monitoring: There are many ways the public can get involved in supporting Bald Eagles through community science and monitoring efforts:

- eBird & Audubon Christmas Bird Count: Volunteers track seasonal sightings to help scientists map population density and wintering shifts.

- NestWatch: A Cornell Lab project where citizens monitor local nests to record timing and number of fledglings.

- Eagle Cams: Live-streamed nests provide invaluable data on nesting success and public engagement.

Key Threats to Bald Eagle Populations Today

- Poisoning: Eagles often scavenge gut piles left by hunters; if lead ammunition was used, the eagle can ingest lead bullet fragments, leading to fatal toxicity. Rodenticides can also poison bald eagles

- Habitat Fragmentation & Prey Availability: Shoreline development for housing and industry reduces the availability of the massive “super-canopy” trees required for nesting and prey.

- Collision Risks: Increased infrastructure, including power lines and wind turbines, poses a physical hazard to low-flying eagles or those focused on prey.

Bald Eagle Wildlife Snapshot Infographic

This infographic offers a quick look at the bald eagle’s defining traits, conservation status, and vital role as an apex predator in the North American landscape.

Bald Eagle Coloring Sheet & Activities for Kids

Download and print this free bald eagle worksheet and coloring page to help kids learn about bald eagle habitat, diet, life cycle, and conservation through hands-on activities that build science knowledge, vocabulary, and curiosity. Perfect for classrooms, homeschool, libraries, and nature-loving families, these printable bald eagle activities turn learning about America’s national bird into an engaging, screen-free experience

Sources (Alphabetical)

- All About Birds (Cornell Lab of Ornithology) – Bald Eagle

- American Bird Conservancy – Bald Eagle

- American Eagle Foundation – Bald Eagle Biometry

- Center for Conservation Biology — Bald Eagle Nesting Biology

- IUCN Red List of Threatened Species — Haliaeetus leucocephalus

- National Audubon Society — Guide to North American Birds

- U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service — Bald Eagle Overview